Throughout childhood and until about the age of 30, muscles grow larger and stronger. In adulthood, we may begin to lose muscle tissue. In those who are physically inactive, muscle mass declines between three and eight percent each decade after the age of 30 and increases to five and 10 percent each decade after age 50 (Flack, Huber; 2011; Marcell; 2003). This age-related loss of muscle mass and function is called sarcopenia.

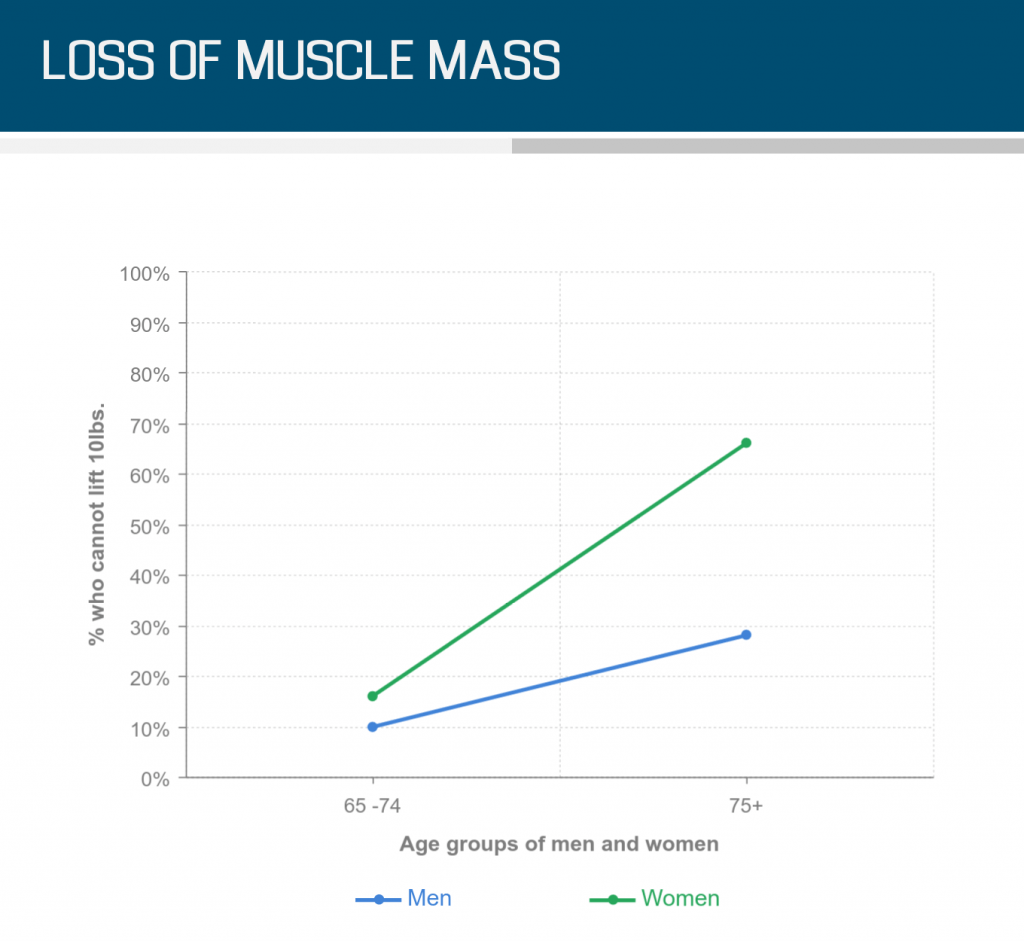

Loss of muscle mass is important because there is a strong relationship between muscle mass and strength. Between 30 and 50 years of age, changes in muscle mass, power and strength are minimal. After age 50, those who are inactive can experience a 15 percent loss of strength per decade (Keller, Englehardt; 2013). Of those 65 and older, 16 to 18 percent of women and eight to 10 percent of men in the United States cannot lift ten pounds, bend forward to pick something up off the ground or kneel down to the floor. After the age of 75, this increases to 66 percent of women and 28 percent of men being unable to lift more than ten pounds (Clark, Manini; 2013). With our aging population increasing in numbers, working longer and the desire to age well at home, this is of serious concern.

Muscle strength is strongly correlated to physical independence and fall prevention. Loss of muscle mass and strength is related to functional impairment and an increased risk for a fall. Leg strength, particularly the ability to rise from a chair, has been found to be a major predictor of frailty and mortality. Leg strength and walking gait speed are two variables predicting fall risk. Additionally, muscular endurance necessary to maintain balance under multi-task conditions such as cooking, gardening or recreational activities, and the importance of muscular power in reactive balance such as slipping on ice or tripping over a curb are important fall risk factors in older adults.

While a sedentary lifestyle and decreased physical activity does play a role in loss of muscle mass and strength, additional factors that contribute to sarcopenia are:

- Reduced communication between neurons, nerve cells in the brain and muscles

- Decreased ability to use protein to rebuild muscle

- Decreased hormone production impacting the maintenance and repair of muscle tissue

Aging impacts specific types of muscle fibers differently. With advancing age, the human body loses fast-twitch muscle fibers at a greater rate than slow-twitch muscle fibers. Slow-twitch muscle fibers are responsible for muscular endurance. These are muscle fibers recruited when going for a walk, working around the home or standing for longer periods of time. Fast-twitch muscle fibers are responsible for actions that require faster, more powerful bursts of movement. Being able to react quickly, such as tripping on a carpet, slipping on wet tile or needing to get out of a chair quickly to stop a pot from boiling over, all require the quick muscle firing that happens within fast twitch muscle fibers.

Loss of balance and speed of movement with age may be the result of changes in the way neurons in the brain send signals to the muscles to initiate movement. As fast-twitch muscle fibers atrophy, neurons re-connect with slow-twitch muscle fibers to prevent the deterioration of muscle. Compared to fast-twitch muscle fibers, slow-twitch muscle fibers:

- Have slower firing rates

- Are slower to contract

- Produce less muscle force

- Are smaller in size and fiber number

The decrease in the fast-twitch neuro-muscular connections, and the increase of the slow-twitch neuro-muscular connections cause a decline in muscular strength and power, resulting in:

- Decreased movement precision

- Decreased production of force

- Slowing of muscle mechanics

- Decreased reaction time