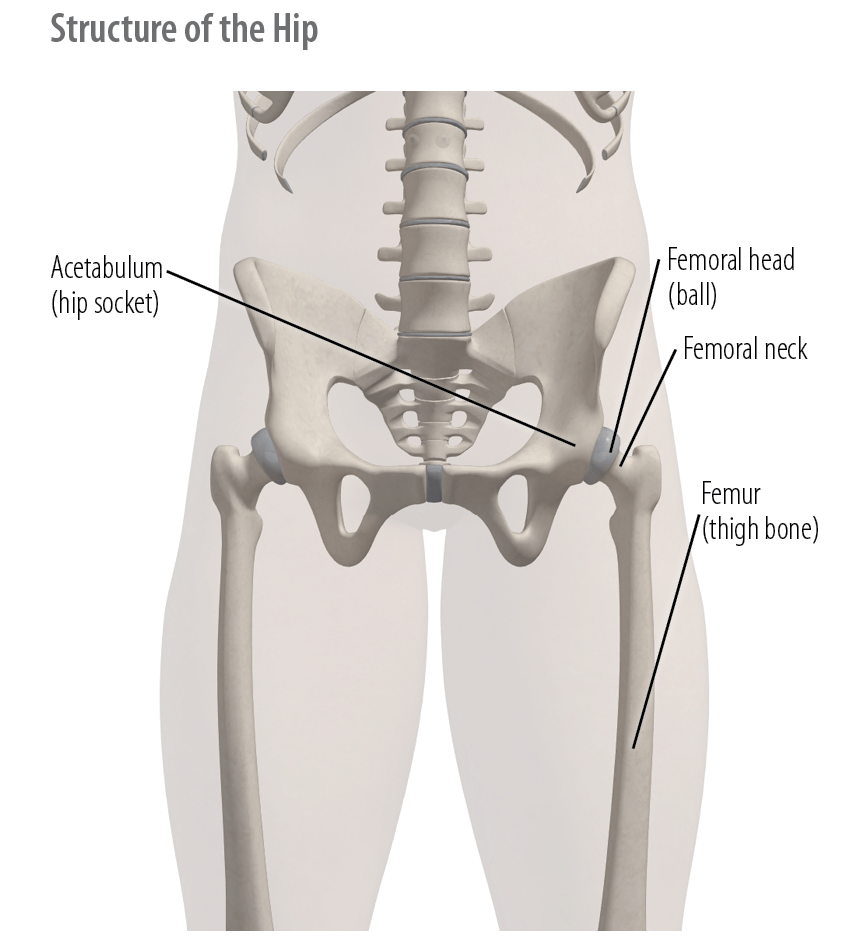

The joint of the hip is formed where the head of the femur (top of thigh bone) inserts into the cup-shaped portion of the pelvis bone, called the acetabulum. Both the ball portion of the head of the femur and the inside of the cup shaped acetabulum are lined with articular cartilage which allows for near frictionless movement.

The hip joint is a ball and socket joint. The design of the hip joint allows for a weight-bearing function. The head of the femur sits deep inside the pelvic acetabulum, surrounding the femoral head.

Instructor tip: As a visual aid, make a fist with one hand and place your knuckles into the C-shaped palm of your other hand, wrapping your fingers and thumbs around your fist. The deep insertion provides greater stability to withstand high compression forces while the ball and socket design allows for movement forward and backward, side to side, and circular, or in rotation.

Muscles of the Hip

Being familiar with the muscles surrounding the hip joint will help you to better program balanced exercise for flexibility, strength, and function, the key training principles for healthy hips.

The muscles of the hip joint complex include:

Muscle

Description

Action

Adductor brevis

Adductor longus

Adductor magnus

Complex of three powerful triangular muscles on the inside of the thigh connecting the femur to the pelvic girdle

- Hip-leg adduction

- Hip-leg external rotation

- Hip-leg internal rotation

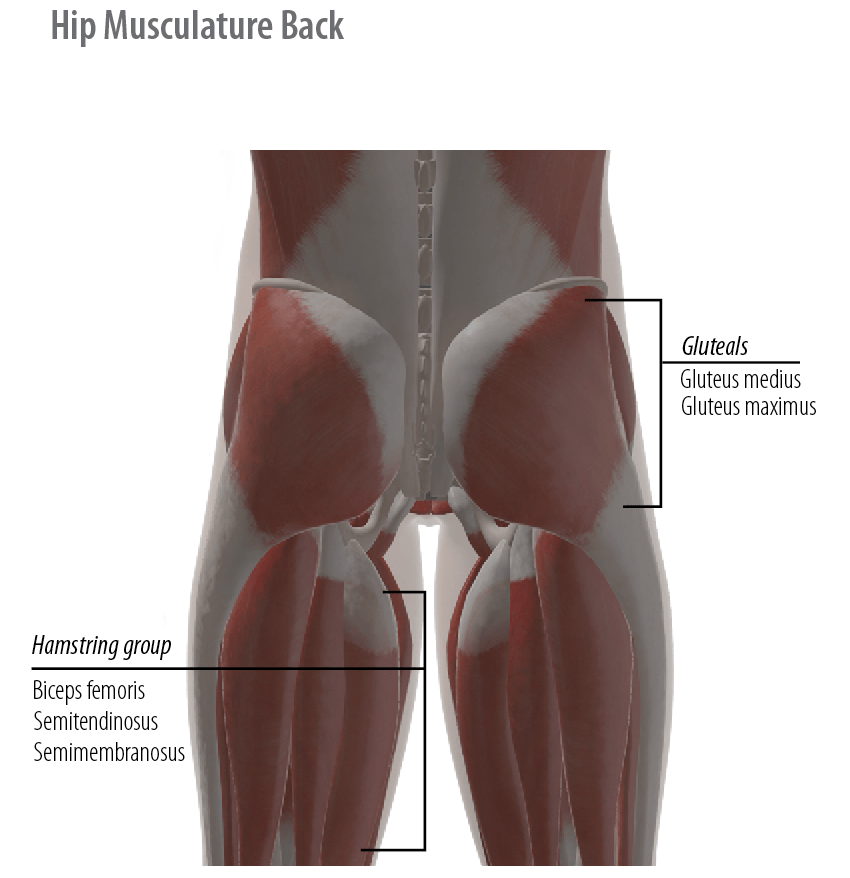

Gluteus maximus

Gluteus medius

Gluteus minimus

Three muscles that form the “glutes”, connecting the head of the femur to the pelvic girdle

- Hip-leg extension

- Hip-leg external rotation

- Hip-leg abduction

Iliacus

Psoas major

Psoas minor

A grouping of muscles that commonly form the iliopsoas; connecting the inside top of the femur and ilium (widest part of the hip bone) and lumbar area of the spinal column

- Hip-leg flexion

- Hip-leg external rotation

- Hip-leg abduction

- Hip-leg stabilization

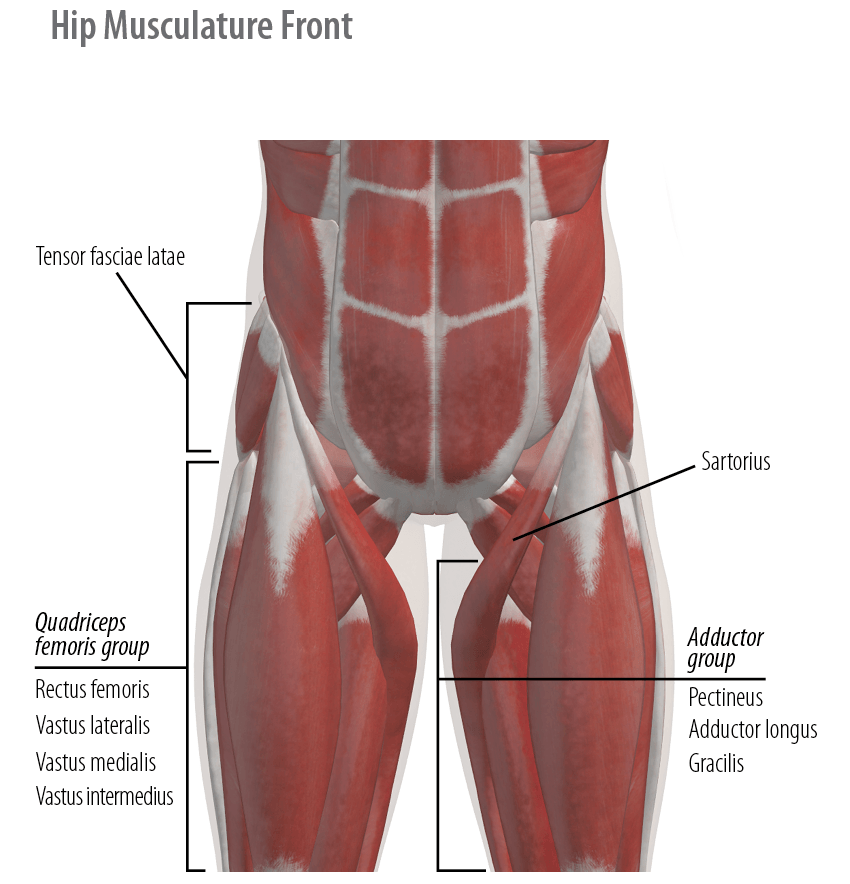

Tensor fasciae latae

A short muscle on the lateral aspect of the thigh, generally connecting the outside of the ilium, down the outside of the femur, continuing to the knee joint

- Hip-leg abduction

- Hip-leg flexion

- Hip-leg internal rotation

Gracilis

Superficial muscle on the inside of the thigh connecting the ischium (lower “wing” of the pelvic girdle) to the lower end of the femur at the knee joint

- Hip-leg abduction

- Hip-leg flexion

- Hip-leg internal rotation

Sartorius

The longest muscle in the body, from the outside of the pelvic girdle crossing the front of the femur to the inside of the knee joint

- Hip-leg flexion

- Knee flexion

- Hip-leg external rotation

- Hip-leg abduction

Gemellus inferior

Gemellus superior

Obturator externus

Obturator internus

Piriformis

Muscles of the hip that hold the femur into the acetabulum

- Hip-leg external rotation

- Hip-leg extension

Quadriceps

Muscles connecting the hip and knee joint

- Hip-leg extension

Hamstrings

Muscles connecting the hip and knee joint

- Hip-leg extension

- Knee flexion

Hip Movement

As a ball and socket joint, the hip can move a variety of ways.

Abduction – Movement away from the midline of the body.

Exercise example: Standing side leg lift

Adduction – Movement towards the midline of the body.

Exercise example: Squeeze ball between thighs

Flexion – The action of moving a joint so that the two bones forming it are brought together.

Exercise example: Alternating knee lifts

Extension – The action of straightening or extending a joint, usually applied to the muscular movement of a limb.

Exercise example: Standing rear leg hip extension

External Rotation – A movement at a joint that causes rotation of the limb away from the midline of the body.

Exercise example: Rotational squat in the transverse plane

Internal Rotation – A movement at a joint that causes rotation of the limb towards the midline of the body.

Exercise example: Seated or standing, leg extended, rotating from hip, turn toes in towards midline of the body

Training for Mobility and Stability

To maintain healthy function of the hip joint, it is important to train both joint stability and joint mobility. Joint stability is defined as the ability to maintain or control joint movement or position. Joint mobility refers to the degree of movement before restriction by surrounding muscles, ligaments, and other tissues.

For example, your class participants may enjoy going for a hike. Both hip joint mobility and stability allow for this activity but the principles are more evident in different aspects of the hike. Hip mobility allows for range in walking gait to ascend and descend the trail and navigate around boulders and trees. Hip stability helps to set the pace and not propel down the trail out of control. Hip stability endures the compression forces of the walk or climb. Hip mobility allows you to jump off the trail if you see a snake! Both hip stability and mobility work together if you trip over a root on the trail, as you need the agility and strength to recover quickly and the stabilization to prevent the fall.

While health- and skill-related principles of training work together to improve mobility and stability, training for hip stability generally involves developing muscular strength, endurance, flexibility, and static balance of the muscles surrounding the hip. Training for hip mobility typically involves more of the skill-related fitness components such as agility, dynamic balance, coordination, speed, reaction time, and power.

Health-Related Fitness Components

Skill-Related Fitness Components

Muscular strength

Agility

Muscular endurance

Balance

Flexibility

Coordination

Speed/reaction training

Power

Exercises that train for stability are generally anchored exercises such as a stationary squat, with both feet on the floor. Exercises that train for mobility generally have more movement, such as an alternating squat side-to-side. Hip muscles and more specific movement training will be discussed in greater detail later in the course.